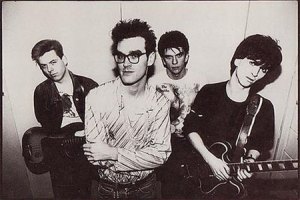

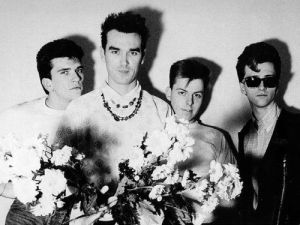

Catchy, recurrent guitar riffs that spiral recursively. Intoxicating, excoriating, venomous lyrics. Morrissey’s caustic wit and sharp, poignant observations. Allusions to Keats and Yeats and Wilde! Oh, yes — The Smiths.

It has been a long time since my ears kept company in any serious way with Johnny Marr and Stephen Morrissey. Periodically we reconnect. My heartfelt thanks go to two younger colleagues who were embarking on a listening excursion with this great band of the 1980s and who piqued my interest. One asked me whether I had ‘heard of this band called ‘The Smiths’’. At first I was vaguely insulted – wasn’t that like asking an art enthusiast whether or not they had heard of Van Gogh? But of course, she was not to know my personal history and the significant place this band had for many teenage would-be intellectuals wearing black. I probably confused her when I broke out in song right there in the staff room – “I would go out tonight, /but I haven’t got a stitch to wear!” – while waving a mimed bunch of gladioli (‘This Charming Man’). Call it end-of-year insanity, but I suddenly had a craving for The Smiths. I wanted that distilled sense of being deliciously miserable, of calling up the ghost of black-dyed hair and eight-up Docs. Mere nostalgia? Perhaps. But The Smiths were a cut above, and across the years the songs have remained architectural and whip-smart.

A friend of mine has been undertaking studies in psychology and has been immersing herself in the principles of behaviourism and association. Music has tremendous associative power. I am sure she would have something to say about this, because in listening to The Smiths again, something strange seems to happen – I am not just listening to a band and its songs. I am listening to a mood intrinsically linked to the landscape of my late teens.

The high school I attended was set back from an eight lane highway that swooped past on its way out to the Yarra Valley and Mt Dandenong. There was a dilapidated drive-in just up the road, still barely functioning. Australia was deep in recession and unemployment ran high. Factories closed. The banks were in strife. People’s parents lost their jobs. I find myself recalling impersonal political realities bound up with the sounds of Manchester indie pop: Thatcher’s Britain, the miners’ strikes, Reagan. These blend with personal memories: the last two years of High School and the friends I shared a love of this kind of music with. I also remember a distinct sense of having to get out of there. Real life was happening elsewhere. Where we were was long grass on unkempt verges, souped-up cars, and a little second-hand bookshop near the train station. The fact that youth unemployment ran at around 50% and that around 30% of our school’s graduating class would fail the VCE seemed only to confirm our dire predicament.

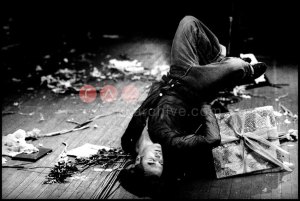

It is hard to distinguish fact from adolescent fancy in these memories. Of course, the emotions conjured by The Smiths are those perennially relevant to early adulthood – awkwardness, romantic longing, alienation, sudden insights, loathing of all conformity and compromise, especially that done by oneself. Morrissey’s lyrics playfully poke fun at the overdone dolefulness of goth-mods: “A dreaded sunny day/So let’s go where we’re happy/And I meet you at the cemetry gates” (‘Cemetry Gates’). This is the enduring charm of these songs: the recognition of sadness with an ironic puncturing of earnestness. Wry, sardonic, gleefully sarcastic, Morrissey articulates the double-bind of one who feels painfully and yet also feels that nothing is authentic. The reference to Wilde in ‘Cemetry Gates’ is not accidental. Morrissey, with his flamboyant stage presence and overt construction of a persona, borrowed from Wilde’s aesthetic. He also clearly references the romantic outlook of Keats, but as a sort of frustrated transplant to the suburbs – Intimations of Banality.

In addition to recycling meanings associated with The Smiths, I find myself adding new slants. For example, one of my favourites, “What Difference Does it Make?”, was (and still is) treasured by me for its sharp, insistent guitar riffs and the little refrain, “Well, I’m still fond of you, oh-ho-oh.” The precise story it told was of less interest to me than the overall tone of the piece – regret and pride and bitterness and the ashes of love. Now that I give it a closer listen, what I casually thought was a song about leaving an abusive, manipulative friendship is now cast in a different light. Sure, there is “I stole and I lied, and why? Because you asked me to”, which seems to confirm the thesis. But what about “All men have secrets and here is mine/So let it be known/For we have been through hell and high tide/I think I can rely on you …/And yet you start to recoil/Heavy words are so lightly thrown”. This is followed by “So, what difference does it make?/…/It makes none/But now you have gone/And your prejudice won’t keep you warm tonight.” The story I sketch in now still has a power struggle: the singer feels that he has been coerced into doing wrong for someone he loves. But the love is complicated and secret –and rejected on the grounds of ‘prejudice’. Is this a coming-out tale — “But now you know the truth about me/You won’t see me anymore”?

On the other hand, “Ask” is a late Cold War timepiece, and continues to be, “Because if it’s not Love/Then it’s the Bomb … that will bring us together.” Not to mention the grimacing “Bigmouth Strikes Again”, which is unchanged in its portrait of murderous politeness: “Sweetness, sweetness, I was only joking/When I said I’d like to smash every tooth/ In your head.” Another serve of sarcasm in “Hand in Glove” cuttingly remarks on every lover’s belief in their uniqueness: “No, it’s not like any other love/This one is different – because it’s us”. Giving them another listen certainly means one finds the many of the same things again – but the strength of the songs continues to be the piquant combination of sounds and moods in tension. There are sharp, highly-defined guitar, drum and bass against a wash of effects; or the apparent self-pity of many of the lyrics is undercut by mordant jabs. I suspect that the chemistry came from two talents that were basically opposed but which, for a period of a few years, found a way to combine.

Johnny Marr has had a substantial solo career – he recently recorded on the Inception soundtrack. The more iconic Morrissey has had only sporadic artistic output since the late 1980s. Marr was the musical genius behind The Smiths, even as Morrissey caught the imagination with his whimsy and vitriol. The combination of these two talents sparked an astonishing sound. They produced seven albums in just five years. In one of those mutations that pop culture throws up, a cover version of “How Soon is Now?” from ‘Hatful of Hollow’ was used as the theme song for the TV series Charmed.

And as for that group of friends? Dispersed. And I did move away. I finished the uni course, got addicted to literary study, did postgraduate work, lived the life of a sessional academic, got tired of the impermanence and grinding poverty of that, went back to uni, qualified as a teacher and took up a second career in the school classroom. I have married someone who had something of a parallel youth, listening to the same songs (and some different ones) in another suburb before we met. Of course, it wasn’t only The Smiths (who had already broken up by the time I was being introduced to them from friends’ mixed tapes). There were The Charlatans, The Pixies, The Stone Roses, The Cure, Joy Division, New Order, and Echo and the Bunnymen. I continue to meet people for whom music is an important ingredient in their life. And the songs? Next time I go on a Smiths bender I expect some will be the same and some will have changed. Our past changes as we change.